Confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been diagnosed in five Nebraska counties and are growing at an alarming rate. They just happen to be the same counties where meat processing plants are found. And two of these counties are located in northeast Nebraska.

The interconnectedness of our lives has been in the spotlight recently. If we could go about our business without effecting others there would be no such thing as a pandemic. We would have all the personal freedoms in the world. But, for better and worse, this is not the case. We are tied to each other financially, emotionally, and spatially. We are now, and have always been, a species of community. The mere survival of our species has always and will continue to depend on our ability to trust each other.

Some of us are able to work from home, which means that social distancing is usually not a problem. But many of us have jobs where this is not an option. To work means to physically be in the space of others. For some, this contact may be limited; for others, they may come in contact with hundreds of individuals. This close contact with multitudes of other people is a problem for it is the easiest place to spread diseases. Without proper measures in order to hinder the spread, hot spots begin to grow, and communities begin to get sick.

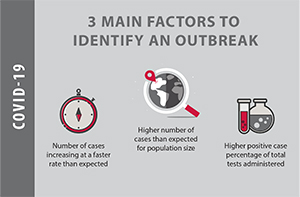

There are 3 main factors that identify when an outbreak is occurring. First, the number of cases must be increasing at a faster rate than expected. By looking at the cumulative number of cases for each county and assessing how quickly the confirmed cases pile up, we can easily compare the counties to each other.

Second, there must be a higher number of cases than expected given the population size. This is identified by the case rate. The rate is calculated by the number of cases for every 1,000 residents who reside in a county.

Third, we need to look at how many of the tests have positive results. The positive test rate is the percentage of positive results out of the total number of tests that were administered. A higher positive case percentage is indicative of a larger pool of infected members within a community.

Table 1 shows the average number of daily cases for the counties with the fastest case growth rate. Figure 1 displays the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases for the 12 Nebraska counties with the fastest case growth. Since the virus was detected in each county at different times, the graph begins when it reached 10 confirmed cases in each county. Notice that there is a clear delineation between the 5 counties where the virus has been detected at the fastest rates and the remaining 7 counties.

Table 2 shows the 8 top counties according to their case rate. Notice that these counties are either in the group of fastest growing confirmed cases or those whose residents commute most to those counties. Statewide, the case rate is 1.09 per 1,000 people. It is interesting to note that the three most populous counties, Douglas, Lancaster, and Sarpy, have case rates between 0.4 and 0.9 cases per 1,000 residents.

The final method used to explore possible outbreaks is based on the percentage of administered tests that have been confirmed. From my previous article on testing1, we know that test supplies tend to go to places where there are more positive results, though there has been an effort to broaden testing in recent weeks. As a higher positive rate is found, more tests are performed. Note that 14.8% of all tests in Nebraska have been confirmed as positive. All 5 of the counties with the fastest case growth rates are represented in the Table 3.

The story here cannot be that the infections are merely spreading at home and within communities. If that were true, why would we not see cases growing more rapidly in Omaha and Lincoln? The speed at which we are finding infection in Dakota, Dawson, Hall, Madison, and Saline counties is not the same as other counties with a similar population size. Is it a coincidence that there are 5 counties in Nebraska with meat processing plants and these 5 counties have the fastest case growth, the most cases given their population, and the highest percent of positive tests in the state?

Let me be clear: I am not advocating for the shutdown of these facilities. The people who work there need their jobs and farmers need to sell their livestock. At the same time, a corporation must be able to protect its workers. To invite people in to work where an infection is rampant, and to send them home to spread the disease among their family is a recipe for disaster.

We must remember that one-to-two weeks after the cases start to rise, we should expect an increase in the number of hospitalizations. A week later, these counties can expect to see an increased number of deaths. Hall County, which has had the longest outbreak, has reported 35 deaths, 10 of which were announced by health officials on April 29. That accounts for 51% of all deaths in the state.

No one knows what to expect with this pandemic. But now, especially in northeast Nebraska, we must remain vigilant. We must not let our guard down. If Dakota and Madison counties follow the lead that Hall County is paving, we are up against a mighty struggle for a while longer. If we are able to make the right moves, and make them soon, we can save lives.